The old BSA has been in the family for as long as anyone can remember, but neither my mother nor my uncles could recall exactly when it was acquired. They told me that as kids, it was as much a tool as a source of recreation to them when they lived on a farm in Natal. There was no need to lock firearms away back then, so it stood at the ready in one corner of the kitchen. Apparently, this turned out to be handy when the cat dropped a mouse under the kitchen table while my grandmother was preparing dinner one evening. Still extremely alive the rodent made a dash in her direction. With an ear-piercing shriek that sent the cat diving for cover, she wielded a broom with abandon and succeeded in upsetting the stew pot, but failed to stop the mouse scuttling under the hem of her dress and up between her petticoats to wriggle against her thigh. By then the rest of the family had rushed to the scene and were splitting their sides laughing, but they had to assist when my grandmother fainted. After my mother winkled the mouse out, Pat got it with an instinctively aimed pellet as it was speedily exiting the kitchen door. He said it was probably his finest shot ever.

Apart from plinking at cans, despatching pests and stocking the larder, the gun was also used to shoot my uncle Bob when he was about 8 years old. Exactly how this happened is shrouded in some mystery, but a friend of Bob’s was visiting and my mother had just returned from school with a cake she had baked in home economics class. Just then Bob ran in white-faced, to say he had been shot. His friend had disappeared never to be seen again and with Bob sitting on the handlebars wanting to know if he was going to die, my mother tore off on a bicycle to fetch her father. Bob was taken to hospital where the doctor took an hour to dig the pellet out of his chest and he carried a large scar for the rest of his life. During the drama Denise, Pat and Allen scoffed every last crumb of the cake, which cheesed Bob off no end. To my grandparent’s credit they did not ban the use of the gun because of the accident, recognising that it was a human, not the gun that made the mistake. If anything, it made everyone more safety conscious.

Pellet guns invariably experience intervals of inaction when their owners grow up and graduate to rifles and shotguns. Although the BSA was lent to family friends occasionally, it eventually lay dormant for the long periods between our family holidays, when I would covetously carry it around and be allowed to use it for a few short days on the farm. It was hard to leave it behind when we had to go back to the highveld. I was told I was too young to have it then, but one day it might be mine.

My mother and Pat must have had some discussion about the right time to let me own an air rifle and had settled on ‘after I had turned ten’, but the exact time was not specified. I had however, overheard a telephone conversation and I knew Pat planned to stop over en route to Northern Rhodesia a few months after my 10th birthday. Nothing had been said about the gun but maybe, just maybe, he would bring it along and the uncertainty and anticipation was almost unbearable. At night I kept having dreams where a distant treat kept appearing and then melting away as I reached out for it. During the day I minded my manners, washed behind my ears and ate all my peas.

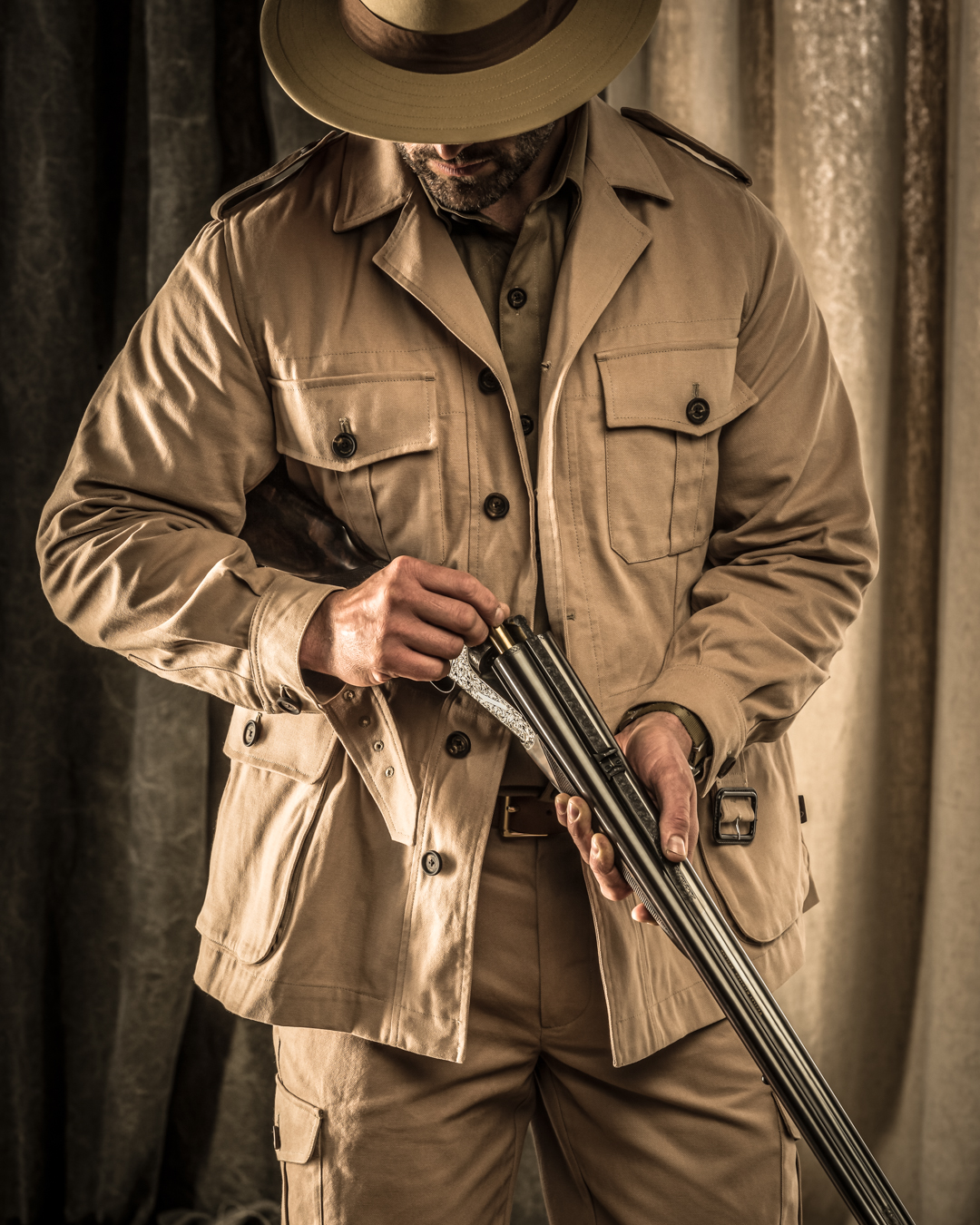

My uncle Pat arrived very late one night after I had fallen asleep, despite valiant efforts to keep awake. He was known for a long morning lie-in and his ability to consume oceans of tea before rising, so I had to be restrained from bursting into his room the next morning. Eventually the door opened and I hurtled in only just remembering to say hello politely before asking if he had brought his rifle with him. A slightly cruel smirk appeared on Pat’s face and he scratched his head saying that he was in such a rush he had left it behind. My face fell and all joy had gone from the day. “I did bring you some trout flies and a book” he said. My thanks were hollow and insincere and the weight of disappointment made my shoulders sag as my voice rose tremulously demanding to know how he could forget the pellet gun. “Oh”, he replied. “I thought you meant my .22 rifle. I think I might have remembered to pack the pellet gun”. He pulled out a soft canvas bag and suddenly it was in my hands; lightly oiled, gleaming and smelling of ‘adventure’.

Despite having used the gun under supervision before, I again had to endure a long lecture. Bob’s accident was recounted and dire predictions were made about my fate should I ever shoot anyone. Discovering that my mother had a very creative imagination when it came to punishment focussed my attention and most of what they said sank in. Next, a list of allowed quarry was recited. It included Indian mynas, mousebirds, fiscal shrikes (because they terrorised the weavers nesting in the garden), rats and mice. Outside town, doves were fair game and finally I was told that in the case of birds, ‘If you shoot it, you eat it’. So began a new era for that veteran old gun.

I wish I knew how many shots of ‘various calibres’ I fired through that barrel. I was alternately John Wayne or a Red Indian Chief or a famous war hero or explorer depending on what movie we had seen at the drive-in and in my imagination, the BSA was alternately a Winchester, a shotgun, a double rifle and sometimes even a machinegun. Cans and various other targets were set up and engaged in the back yard and none of the neighbours ever complained. I must also admit that many birds met their fate and I’m not totally proud of all of them, but nearly every one was eaten. I earned a rare hiding after crippling a thrush, which was not ‘on the list’ after my father noticed it hopping around the lawn on one leg. My backside recovered and so did the thrush because it was still around the next year.

The day my friend next door was given a ‘Gecado’ air rifle, the safaris really began and we cycled to the nearest open spaces to hunt doves or field mice and collect bird eggs. The hunt that remains clearest was sparked when my father remarked that in a book he’d read, an early explorer had recorded a herd of over fifty elephant crossing ‘Linksfield Ridge’. This was long before gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand and before the ridge got named and although its rocky spine is now covered in suburban sprawl, it was still pretty unspoilt when we were young. Most importantly though, we knew guineafowl still ran wild on its slopes.

It was a dawn start, because we planned to detour via some dams on the ‘Jukskei River’ to visit an old hamerkop’s nest before making for ‘Gillooleys Farm’ where we would leave our bicycles. The Egyptian geese had decided not to use the nest that winter so we hunted striped field mice on the dam walls for a while and brewed some tea over a fire that smoked pungently from the ‘khakibos’ kindling we used. Youthfully confident in our shooting skills, we had taken tea, two apples, matches, pocket knives and salt. This was adventure in its purest form. We could get where we needed to be on our bikes and we weren’t expected home till late. By 9.30am, we had ‘tethered’ our trusty steeds in some long thatch grass at Gillooleys. We carefully selected only perfectly formed pellets, keeping a few in our mouths and the rest wrapped in a handkerchief. I checked my rifle because prior to being soldered back on, the catch that locked the cocking lever against the barrel would sometimes slide out of its recessed groove. You could still shoot by clasping the lever tightly against the barrel while sighting, but then you could not ensure that the other small lever to open and close the loading aperture was pressed tight shut with your left thumb. We needed no distractions when hunting where elephant had walked.

Guineafowl are cunning and with pellet guns, we knew we would have to get really close. It was noon by the time we located a small flock and commenced our ambush. They always trotted off uphill if slightly disturbed, so we retreated out of sight and took a wide, circular route to position ourselves higher and far above them. After peeping over some boulders to spot the flock below us, the leopard crawling started. Actually, the slope made it easier and it was more of a slow, slither that took us over dry grass and around rocks towards the prize. After what seemed like hours, a soft ‘chink’ kick-started my pulse. Parting the grass, I saw what looked like the biggest guineafowl in the world ten meters in front of us and I could see the light in its eye. My friend nodded and aiming carefully, I squeezed the trigger. The gun went ‘thwap!’ and there was a corresponding sound from the guineafowl, then I clearly remember seeing the pellet bounce back off it’s wing before it flew off cackling with the rest of the flock. It was much later and with growling stomachs that we managed to shoot a ‘little brown job’. It was so small we ate it bones and all before cycling home.

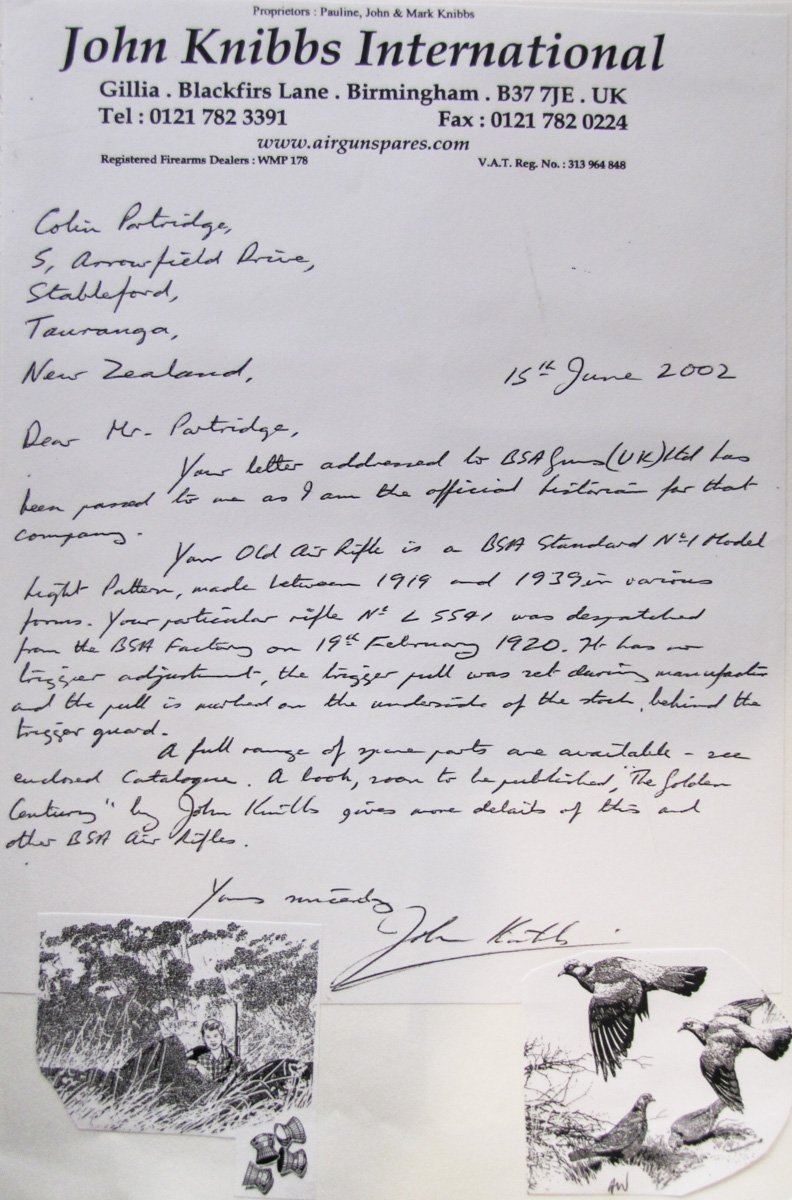

That was all a long time ago and the BSA has of course, got older too. One day a friend gave me the contact details of a person he said keeps the historical records for the ‘BSA’ company. I wrote giving the details of my air rifle, asking if he could supply any information on the old girl. A few weeks later, I was delighted to find a hand-written reply in the postbox:- “Your old air rifle is a BSA standard No1 model, light pattern, made between 1919 and 1939 in various forms. Your particular rifle No5541 was despatched from the BSA factory on 19th February 1920. Yours sincerely, John Knibbs**”.

Last night I gave the old veteran a gentle rub with a lightly oiled rag and put it back in the safe, always ready for new adventures.

** John Knibbs is the official historian for BSA Guns (UK) Ltd and has published a book entitled ‘The Golden Century’ about BSA rifles.

This story is dedicated to my uncles Pat, Allen & Bob, my aunt Denise & my father Jock, but especially to the memory of my mother, Penny who ensured that little boys had fun while growing up.

Enquire

Enquire

Gary Duffey on October 25, 2016 at 10:55 pm

Great account Colin and it brings back many memories! Transition to the pellet gun from the BB gun brought about two primary new possibilities. Squirrels, and Bullfrogs. They have only one thing in common, tasty back legs. Stalking them barefoot was some sport.

Thank you for this story.

Chris Buckingham on October 26, 2016 at 6:51 pm

Many thanks for relating your story Colin, it held my attention right the way through, mainly because it repeats the experiences of my own youth, unfortunately there are few youngsters in this modern "safety police" ruled world that will experience the delight of stalking with an air rifle of their own.