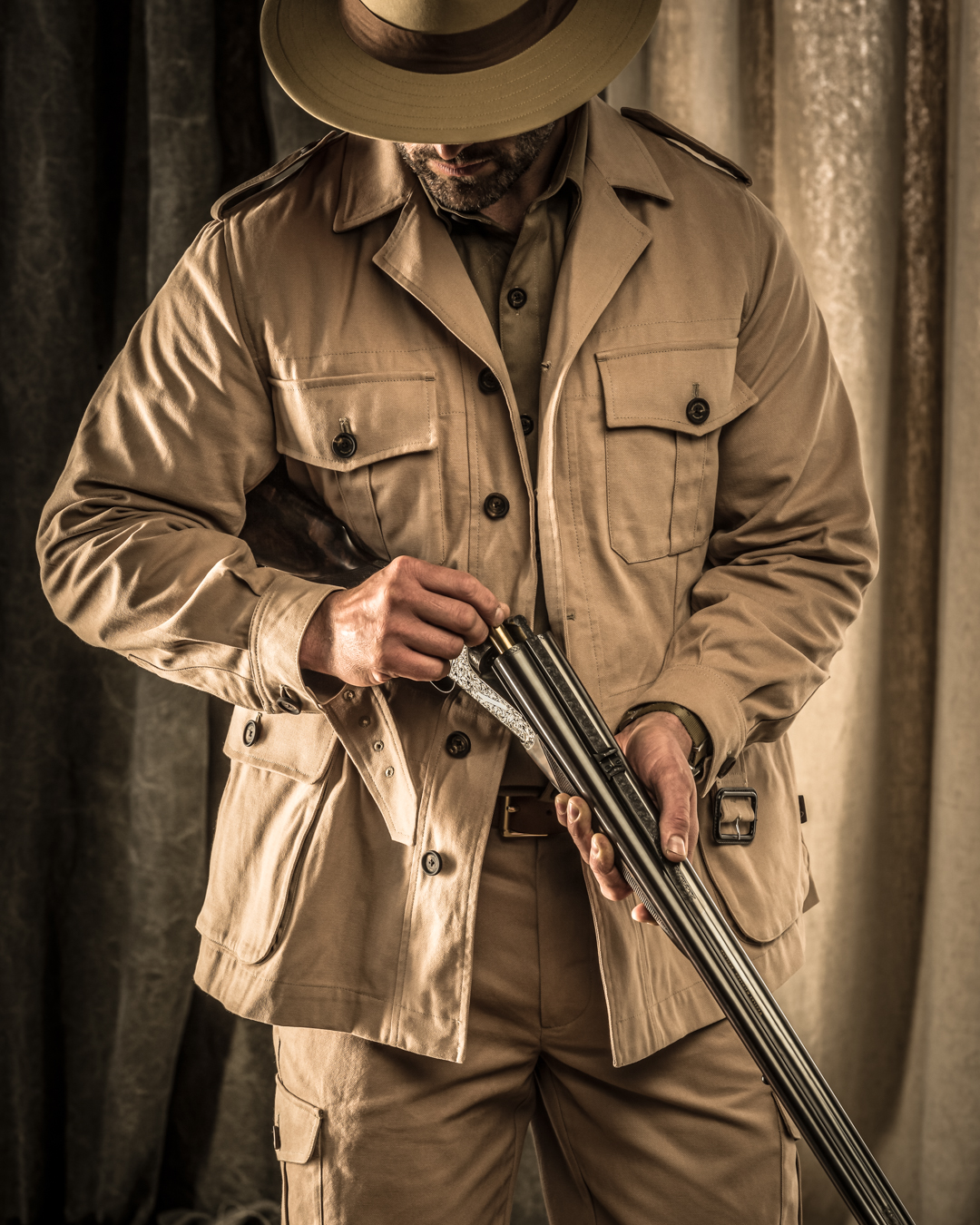

Rip out the flourescent lights and electrical wire, and there isn’t much in this workshop that Haydn’s ancestors didn’t or couldn’t use. Along three south-facing windows is Haydn’s workbench, cluttered with files, chisels, hammers, strips of emery—the sundry implements of traditional handwork.

At the back of the shop are the machines. Haydn flicks on an electric motor, and a line shaft suspended near the ceiling begins to turn, driving pulleys hung with a web of worn leather belts that are connected to lathes, millers, shapers and slotters below. The years roll back as the machines begin to chug and hum, and the Edwardian era is upon you. Here is a belt-driven vertical miller from Germany’s Friedrich Deckel; The Denbigh, another miller from A. Finney & Co.; and yet another from Alfred Herbert. All were in use when Britain’s soldiers marched off to France in 1914.

Haydn appeared bemused at his American visitor’s wide-eyed wonderment. “This is just normal for me,” he said. “I just work from basic machinings I do here, and then make guns with these parts by hand.”

Making guns by hand is what Haydn’s family has done since at least the 1860s. His earliest known ancestor in the gun trade was his great-great-grandfather, John Hill (born in Birmingham in 1844), a gunmaker and engraver who had at least two sons follow on: Jesse Hill (born in 1867) and Charles Hill (in 1877). Jesse—Haydn’s great-grandfather—and Great-Great-Uncle Charles were action filers skilled enough to be recruited to live and work in London by Holland & Holland in the 1890s, when the firm erected its own factory on Harrow Road. In time Jesse became a foreman at Holland’s, and he was joined there by his son, Jesse Jr. (born in 1886), probably in the early years of the 20th Century, because apprentices started work around age 14.

The younger Jesse stayed at Holland’s until just after the First World War, when he moved back to Birmingham to set up as an independent action filer to the trade in the city’s gun quarter—initially on Price Street, later on Steelhouse Lane, and then Great Brook Street. Jesse Jr. was in turn joined by his son, Henry Radford Roland Hill (born 1921 and better known as Harry), and the pair worked together until Jesse Jr.’s death, in 1961. Three years later Haydn was born to Harry, ensuring another generation would continue the family’s profession as action filers (or actioners as they are called today).

The family name Hill suffuses the history of the Birmingham trade—Nigel Brown’s British Gunmakers Volume Two lists 24 separate Hills as gunmakers in the 19th and early 20th Centuries. “I know almost nothing about them,” Haydn admitted, referring to who among them was related to whom, and how and where they lived, worked and died. Like so many craftsmen now forgotten, these were working men who labored in anonymity for larger gunmakers who had established their names as retail brands. In an age that was hierachical and class-bound, those who worked with their hands were seldom recognized; their achievements were even less often celebrated or recorded.

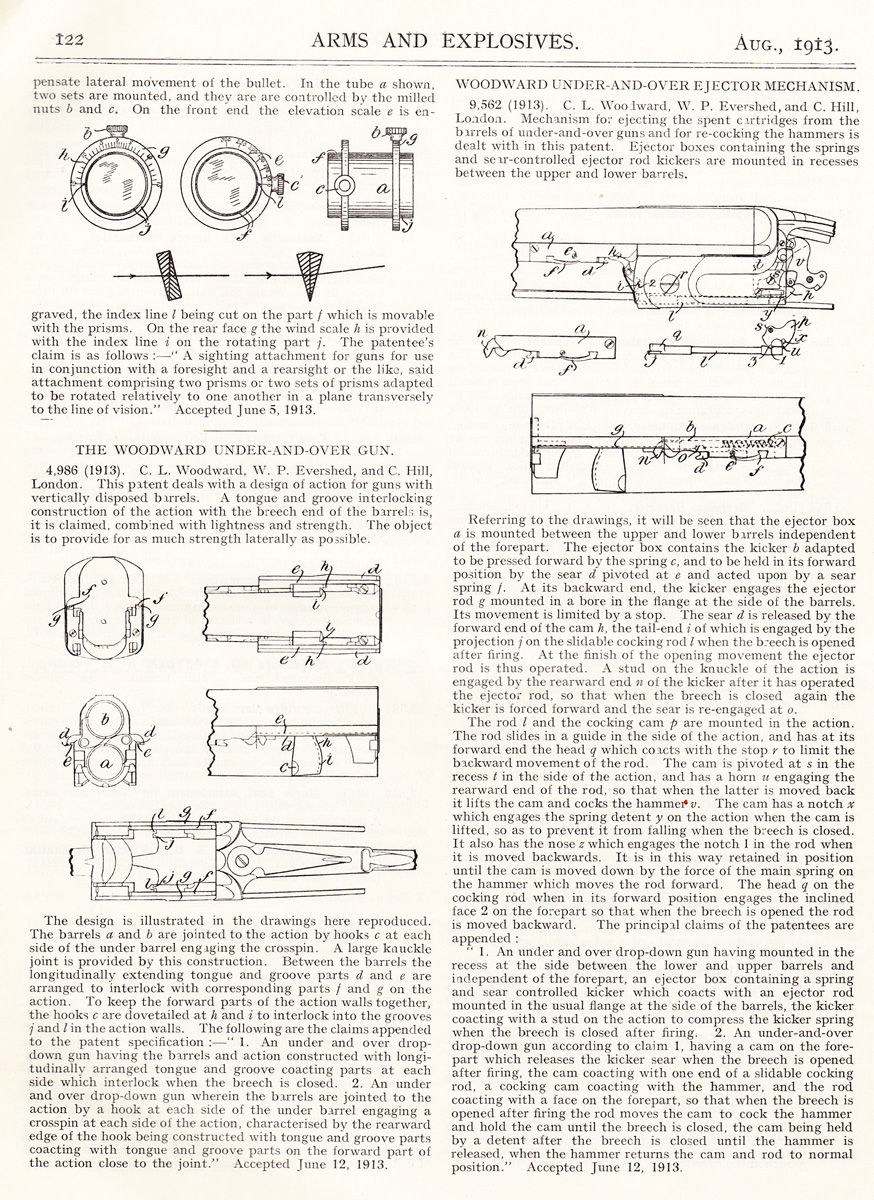

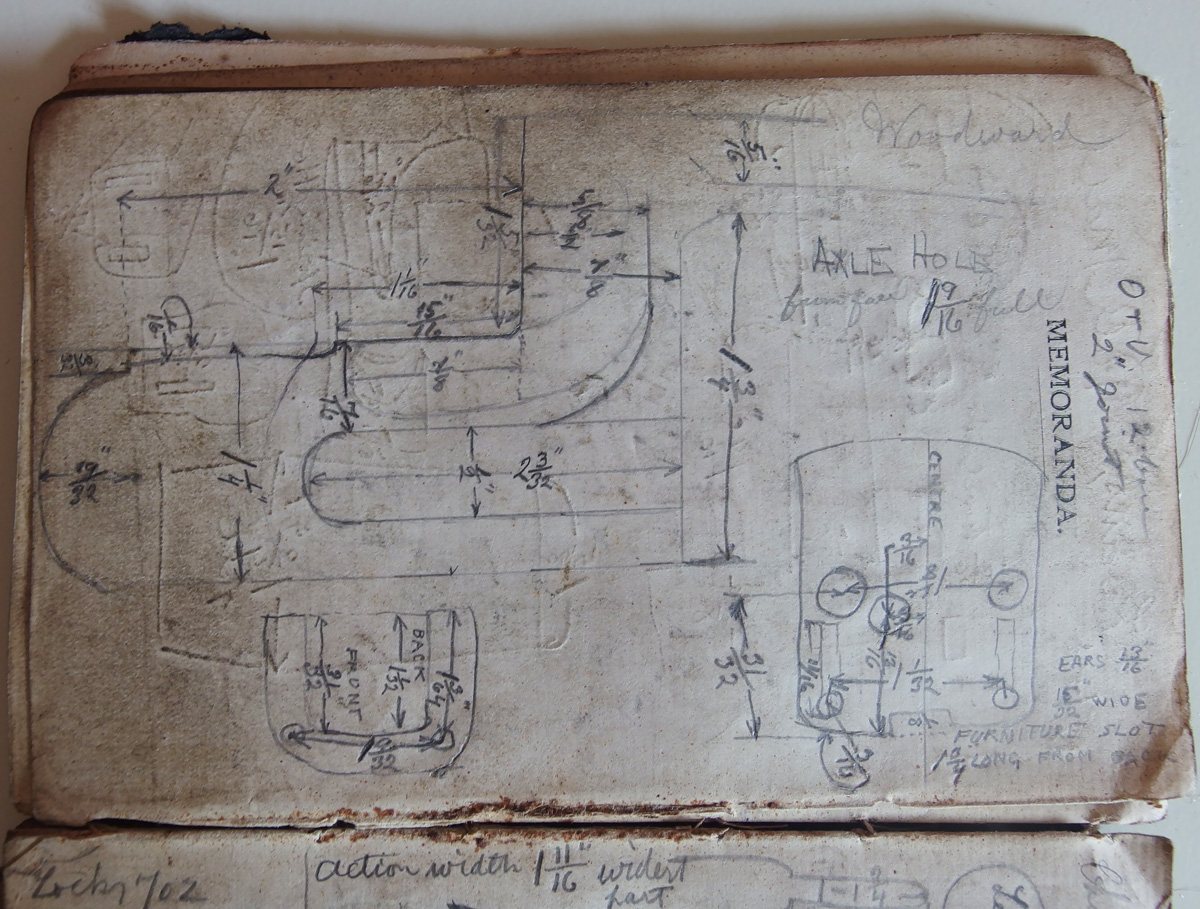

Recognition, if not fame, had come tantilizingly close for at least one family member. From his grandfather’s desk, Haydn pulled a small, tattered black book dating to 1919. It had belonged to his Great-Great-Uncle Charles, who at some point in the early 20th Century had left Holland & Holland for London’s James Woodward & Sons, where in 1913 he co-patented (Nos. 4986 and 9562, with Charles Woodward and W.P. Evershed) the firm’s enormously influential sidelock over/under. Charles has been credited by British gun historians such as Nigel Brown and David J. Baker as being largely responsible for the seminal design, and lore has it that he later left because he felt he had not received enough credit for its creation. Today the gun is not known as the Hill/Woodward over/under, rather only as the Woodward.

Cracking open the book, its pages brittled by time and darkened by generations of fingers smudged with smoke black and gun oil, Haydn pointed to an entry of hand-drawn dimensions for a 12-gauge sidelock over/under. At the top of the page bearing the drawings, in faint pencil in Charles’s hand, was the word “Woodward.”

“Good heavens,” said English gunmaker Robin Brown, who had accompanied me to Haydn’s. “Now that is a page of gunmaking history.”

A cache of correspondence dating from the 1920s through the ’70s and pages from a ledger book revealed just how many of England’s storied gunmakers had used Haydn’s great great uncle, grandfather and father to make their actions at one time or another: Grant, Lang, Hussey, Harrison & Hussey, Beesley, Jeffrey, Rhodda, Gibbs, Army & Navy, Osbourne, Powell, Holloway, Cogswell & Harrison, and Churchill, among others. There were orders for A&D boxlocks; screw-grips of all grades; sidelocks of conventional, Beesley, and Baker-design; double rifles; pigeon hammerguns; and over/unders.

“Best”-quality sidelock over/under actions built to the Woodward pattern—very difficult to make—were evidently a specialty, not only of Charles’s but also of Jesse’s. A letter to Jesse from E.J. Churchill (Gunmakers), Ltd., dated September 5, 1933, for an “urgent order” of an over/under pigeon gun reads as follows: “You have been recommended to us as the most likely person to suit our requirements and we are therefore placing this order with you and if satisfactory several other orders will follow . . . . This gun has to be shipped to New York at the end of November so you will appreciate no time can be lost.”

Jesse and Harry Hill did an enormous amount of work for Churchill’s from the 1930s until the firm closed, in 1980, and, according to Haydn, both knew the charasmatic owner well. In the mid-1950s Robert Churchill tasked Haydn’s grandfather with simplifying, perfecting and building his firm’s new Zenith over/over, a nettlesome triggerplate design that—according to Harry as quoted in Don Masters’ The House of Churchill—“almost drove his father [Jesse] mad.” Said Haydn: “I think my grandfather was under a lot of pressure to make the gun work.”

Despite the Zenith’s noteriety—Churchill promoted it in his popular book Game Shooting, and the story of its development became something of a consuming passion for British gunwriter Geoffrey Boothroyd—only two are believed to have been completed of the five originally envisioned. It was simply too complicated and too expensive to build commercially.

Haydn walked to the corner of his workshop to a bank of wooden drawers, pulled one open and, to the clanking of steel, rummaged through a nest of old actions to extract an over/under-body machining coated in a fine patina of rust. “It’s for a Zenith,” he said. “Never made up.” Then he found a set of barrels, with the breeches sculpted in the distinctive serpentine shape peculiar to Churchill’s gun. I could only imagine what Boothroyd would have thought if he’d seen them.

In 1958, when redevelopment in inner-city Birmingham flattened their premises at Great Brook Street, Jesse and Harry moved to the current workshop, bringing their ancient machines with them. In 1980, at 16, Haydn joined his father, then working alone, and began training under him as an apprentice action filer.

“You’ll have soon finished your apprenticeship,” quipped Robin, who also started work under his father at age 16 at A.A. Brown & Sons.

“There’s always something new to learn, isn’t there?” Haydn replied.

By the early ’80s, the Hills were mostly making sidelocks for the trade. A gunmaker typically would supply them with the barrels made up, machinings for the action and forend, and a set of locks. As actioners, Harry and Haydn would make, fit and regulate the internal components, chamber the barrels and joint them in, file up the action, fit the furniture, and have the gun proofed. The gunmaker-client would then take the action in-the-white back to be stocked, engraved, hardened and final-finished under its own name.

Harry taught young Haydn by allowing him to rough machine small components. “I didn’t take them to the finished stage,” Haydn said. “My father would finish them off by hand. After about a year he decided to push me further on, to actually fitting the parts. Then I moved on to fitting leverwork, ejectorwork, safework, then connecting it all up, until he thought I could do most of it.”

Learning to joint the barrels to the action—that is, the time-consuming, skill-intensive job of mating the bearing surfaces of each to the other—came last. “I was never allowed to do much jointing until later on—after maybe 10 years,” Haydn explained. “Too much at stake; if you scrape a pair of barrels, you’re in big trouble.”

And it wasn’t until his father suffered a paralyzing stroke in 1993 that Haydn began to consider himself a gunmaker in full. “I was thrown in the deep end really,” he said. “One day he was there; the next he wasn’t.”

After his father died, in 2005, Haydn became sole owner of Jesse Hill Gunmakers, and despite ups and downs in the British gun trade, he has never lacked work.

Today Haydn enjoys a reputation as a first-rate jointer, a craftsman who works to best standards and is possessed with a flair for filing up actions with elegance and grace. As an actioner to the trade, he declines to discuss the identities of current clients, but as an example of ongoing work, he revealed a massive large-bore action on his workbench. It was a boxlock with a hidden third-fastener, and Hayden had sculpted it by hand with large bolsters and was still in the process of jointing in its rifled barrels—a difficult job, given its Saurian size and weight.

“How many times have I been in here and you’ve had a moan about it?” Robin said.

“Yeah, yeah,” Haydn replied. “Hard work to joint, it is. Makes my shoulders ache.”

Yet for Haydn, traditional gunmaking—using manually operated machines to mill, drill, slot and rough out components, and then push a file and wield a chisel to literally craft a gun by hand from them—presents not only a challenge to rise to but also an accomplishment to take pride in. “A proper gun is as good on the inside as it is on the outside,” he said.

Haydn has never been asked to make a gun from the CNC-milled, wire- and spark-eroded components made close to final tolerances that are now ubiquitously used in the trade. Would he ever do so? “I would, yeah,” he said. “Can’t turn down work. But I don’t think I’d enjoy it. A machine-made gun is just a kit. It’s not really gunmaking, is it?”

The answer is complex, beyond the scope of this article, but Haydn’s question is an existential one that goes to the heart of artisinal gunmaking’s future—in England, in Europe, in America, everywhere.

At 50, Haydn Hill is still young, as gunmakers go, and his skills ensure years of work to come. “I don’t think there are many jointers out there with my experience.” But he acknowledges that he is among the last of a type: a gunmaker trained before the trade’s adoption of CAD/CAM technology. “Gunmaking—as I know it—is a dying art.”

He will likely also be the last of his line of Hills to make guns in Birmingham. Without a son, he shakes his head at the thought of bringing along an apprentice. “This is the sort of trade where you follow on from your father, who followed on from his, and he from his.”

One day he may consider making a gun or two with the Hill name on it—a handful exist from his grandfather’s day—but “it’s not something I’ve given much thought to.”

In the meantime there are actions to make for others and guns to build. “Well . . .” said Haydn, looking anxious to return to the century-old bench that he has known since he was a boy. “I’ll be here until I drop. It’s all I’ve ever done.”

Author’s Note: For more information, contact Jesse Hill Gunmakers, Ash Tree Rd., Stirchley, Birmingham, B30 2BJ, England.

Vic Venters is Shooting Sportsman’s Senior Editor.

My sincere thanks to Ralph Stuart Editor of Shooting Sportsman Magazine for allowing me to publish, in full, this article by Vic Venters on Haydn Hill.

Finally I would like to add..

"Given that London gunmakers often regard Birmingham craftsmen as little more than blacksmiths it's ironic that one of the world's most expensive shotguns -- the Woodward over/under as built today by J Purdey & Son -- actually has Birmingham origins...."

Simon

Vance Daigle on November 9, 2016 at 11:07 am

Good Day sir,

A good story thank you for sharing!!

In Christ

Vance,

Neill on November 9, 2016 at 11:22 am

This is marvellous stuff, thank you for the article. The workshop really is a period piece, where craftsmanship not computers must reign supreme. I feel like a traitor as a few years back I had DRO fitted on my imperial Myford lathe!

steven nash on November 9, 2016 at 1:58 pm

Fabulous post. Informative and interesting, well written and supported by great graphics. I am amazed you find the time Simon!

Peter Loam on November 10, 2016 at 1:18 pm

This is why I love old English guns. The craftsmanship, the handskill, the knowledge and the sheer bloody inventiveness. Superb article and superb photography. Thank you Westley Richards for the "Explora", it keeps the world aware of the traditions from which our sport has derived it's pleasure. It's just such a damn shame that all the other English gunmakers seem to be leaving it all to you to keep it alive. Is it just laziness, or good old English arrogance?!

Peter on November 10, 2016 at 2:32 pm

This is great social history! establishments like this I personally didn't even dream still existed, what a fabulous survivor, Haydn looks like the type of guy you could talk to about his trade for ever. and the history locked in there, astounding.

Great blog!

David Hodo on November 13, 2016 at 7:51 am

I agree with Peter and Peter (same?) completely. The Explora.com is a treasure Simon. Original copies, both hard copy and digital, should be stored in the British Museum someday.

David Hodo on November 13, 2016 at 7:55 am

On second thought, maybe the British Library would be more appropriate!