One article I was sent I think puts the uproar in perspective, written by a Zimbabwean and published in the New York Times a few days ago.

In Zimbabwe, We Don’t Cry for Lions by Goodwill Nzou

Winston-Salem, N.C. — MY mind was absorbed by the biochemistry of gene editing when the text messages and Facebook posts distracted me.

'So sorry about Cecil'.

'Did Cecil live near your place in Zimbabwe'?

Cecil who? I wondered. When I turned on the news and discovered that the messages were about a lion killed by an American dentist, the village boy inside me instinctively cheered: One lion fewer to menace families like mine.

My excitement was doused when I realized that the lion killer was being painted as the villain. I faced the starkest cultural contradiction I’d experienced during my five years studying in the United States.

Did all those Americans signing petitions understand that lions actually kill people? That all the talk about Cecil being “beloved” or a “local favorite” was media hype? Did Jimmy Kimmel choke up because Cecil was murdered or because he confused him with Simba from “The Lion King”?

In my village in Zimbabwe, surrounded by wildlife conservation areas, no lion has ever been beloved, or granted an affectionate nickname. They are objects of terror.

When I was 9 years old, a solitary lion prowled villages near my home. After it killed a few chickens, some goats and finally a cow, we were warned to walk to school in groups and stop playing outside. My sisters no longer went alone to the river to collect water or wash dishes; my mother waited for my father and older brothers, armed with machetes, axes and spears, to escort her into the bush to collect firewood.

A week later, my mother gathered me with nine of my siblings to explain that her uncle had been attacked but escaped with nothing more than an injured leg. The lion sucked the life out of the village: No one socialized by fires at night; no one dared stroll over to a neighbor’s homestead.

When the lion was finally killed, no one cared whether its murderer was a local person or a white trophy hunter, whether it was poached or killed legally. We danced and sang about the vanquishing of the fearsome beast and our escape from serious harm.

Recently, a 14-year-old boy in a village not far from mine wasn’t so lucky. Sleeping in his family’s fields, as villagers do to protect crops from the hippos, buffalo and elephants that trample them, he was mauled by a lion and died.

The killing of Cecil hasn’t garnered much more sympathy from urban Zimbabweans, although they live with no such danger. Few have ever seen a lion, since game drives are a luxury residents of a country with an average monthly income below $150 cannot afford.

Don’t misunderstand me: For Zimbabweans, wild animals have near-mystical significance. We belong to clans, and each clan claims an animal totem as its mythological ancestor. Mine is Nzou, elephant, and by tradition, I can’t eat elephant meat; it would be akin to eating a relative’s flesh. But our respect for these animals has never kept us from hunting them or allowing them to be hunted. (I’m familiar with dangerous animals; I lost my right leg to a snakebite when I was 11.)

The American tendency to romanticize animals that have been given actual names and to jump onto a hashtag train has turned an ordinary situation — there were 800 lions legally killed over a decade by well-heeled foreigners who shelled out serious money to prove their prowess — into what seems to my Zimbabwean eyes an absurdist circus.

PETA is calling for the hunter to be hanged, Zimbabwean politicians are accusing the United States of staging Cecil’s killing as a “ploy” to make our country look bad. And Americans who can’t find Zimbabwe on a map are applauding the nation’s demand for the extradition of the dentist, unaware that a baby elephant was reportedly slaughtered for our president’s most recent birthday banquet.

We Zimbabweans are left shaking our heads, wondering why Americans care more about African animals than about African people.

Don’t tell us what to do with our animals when you allowed your own mountain lions to be hunted to near extinction in the eastern United States. Don’t bemoan the clear-cutting of our forests when you turned yours into concrete jungles.

And please, don’t offer me condolences about Cecil unless you’re also willing to offer me condolences for villagers killed or left hungry by his brethren, by political violence, or by hunger.

Goodwell Nzou is a doctoral student in molecular and cellular biosciences at Wake Forest University.

Woody Cotterill on August 7, 2015 at 7:12 am

Yes that essay is doing the rounds in the conservation arena too.... Of course it fails to even mention the impacts on the landscape of massive explosion in human densities in rural Africa since the continent's colonization. Less and less fuelwood, arable land and especially potable water might suggest to at least some that traditional livelihoods cannot persist....Then there are the exacerbating human pressure on the remaining habitats of large mammals, especially lion and elephant, is getting worse.

Thus it is the integrity of lion and elephant habitat that is at stake. Reading the writings of the very rapid changes across the tropics, especially central Africa through the past century makes for a depressing experience. As many readers of this medium know too well, most Game dept officers were engaged full time through the latter decades of the 20th century opening up more land for settlement, and neutralizing crop and stock raiders, including those responsible for human causalties. These readings include the books by Richard Harland, Keith Meadows (on Rupert Fothergill) for Zimbabwe; Guy Muldoon for Malawi (Leopards in the Night' The Trumpeting Herd) and Bruce Kinloch for E Africa - The Shamba Raiders. All this recent history is conveniently forgotten.

There has indeed been a huge hallabaloo about this lion! Clearly the PH looks to be guilty of gross corruption in cahoots with the locally-politically-connected on land that was expropriated in the most recent landgrab. Hopefully the wrath of the law will run its full course. The interference and exploitation of circumstance by a safari hunting outfitter of a well respected conservation biology project run under trying conditions deserves all due condemnation. Black-listed and worse!

I agree it is pointless to try and engage the harder-core individuals as they persistently fail to think rationally and care less. There have been some lucid and rational commentaries amidst all the the ranting and arm waving - 2 examples :

http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2015-08-03-cecil-the-lion-lessons-in-misplaced-outrage/#.VcNwgvmqqkp

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/armchair-conservationists-social-media-likers-ian-johnson

Concern over the individual animal and realities of successful conservation are hard to reconcile, especially in the tropics. The individual rights concerns of the more obvious lion or elephant are rather challenging to implement when all of its population can no longer be found in said patch of habitat a few decades or even a mere year or two hence. Again, the main cause of extirpation is not hunting but rural expropriation of habitat, and conflicts with the larger vertebrates, crocodiles included.

Conservation challenges span the hierarchy of biodiversity from genomes to ecosystems, in which the individual organism is a transient albeit critical player. Integrity of the ecosystem, and keystone species are overriding concerns in any scientific strategy; this means maintaining processes from the genetic through to the ecological across landscapes inclusive of sufficient areas of source habitat [sources, unlike sinks, maintaining +ve demography profiles of monitored species]. The flagship and umbrella species have major roles in securing the future of such landscapes especially in elevating $$ returns from wildlands on a par with croplands and rangelands; otherwise the latter are sure to gain the economic upper hand - expanding at the expense of biodiversity. And as is all so very clear, the larger bodied mammals dwindle away as the first victims of remorseless rural development.

An overriding aim in savannas - lion habitat especially - is to maintain the largest areas of intact habitats possible, and mitigate human encroachment on safari and core areas with ecological goods and services etc. This argument is a very well worn one, and it's worked and working - witness Namibia and elsewhere.

Those of us engaging and building on demonstrable successes, in Zimbabwe, with sustainable conservation (won by those far sighted, dedicated pioneers) knew all this all too well by the mid 1980s. The economic crux swings on the balance of land for cattle etc versus wildlife across the Sebungwe Basin etc - it hinged on the ability to sell at least 4 of the Big 5, not only the trophy fees but securing fullest possible bookings on full 14 and 21 day hunts, especially the latter for trophy elephant. A precarious margin indeed!

In closing, to return to my opening point. Rural human populations continue to grow - exponentially. Nevertheless, safari hunting - if professionally and scientifically guided - remains the only hope for much of Africa's wildlands, but more of us fear the successes gained in the dawn in the previous years are long passed, and too much has been lost and set backward. Sadly, the twilight darkens.

Gary Duffey on August 7, 2015 at 8:18 am

Simon, thank you for posting this!

Keith Fahl on August 7, 2015 at 12:42 pm

Simon,

This was an excellent response to the uproar and thank you for posting it.

KF

Neill Clark on August 7, 2015 at 1:23 pm

Simon

A great response indeed. I have found the whole issue bemusing frankly. The USA has massive gun related issues, yet chooses to focus on a single Lion.

Now let me confess;

1. I left SCI because I was tired of the photos of Americans with very beautiful, but very dead, animals in their magazine.

2. Do I believe managed big game hunting is, on the whole, good for conservation? A whole hearted YES.

3. Do I approve of bow hunting? An equally whole hearted NO. If you set out to kill something you have a moral obligation to try and do it as humanely as possible, and we've moved on from bow and arrows.

The media latched on to poor old Cecil, and the bunny hugging fraternity took it hook line and sinker. Would I shoot a Lion or Elephant? No, unless it was me or the beast, would I shoot a Cape Buffalo? Damn right I would, if I could afford to, it's all down to the individual.

Neill Clark on August 7, 2015 at 2:38 pm

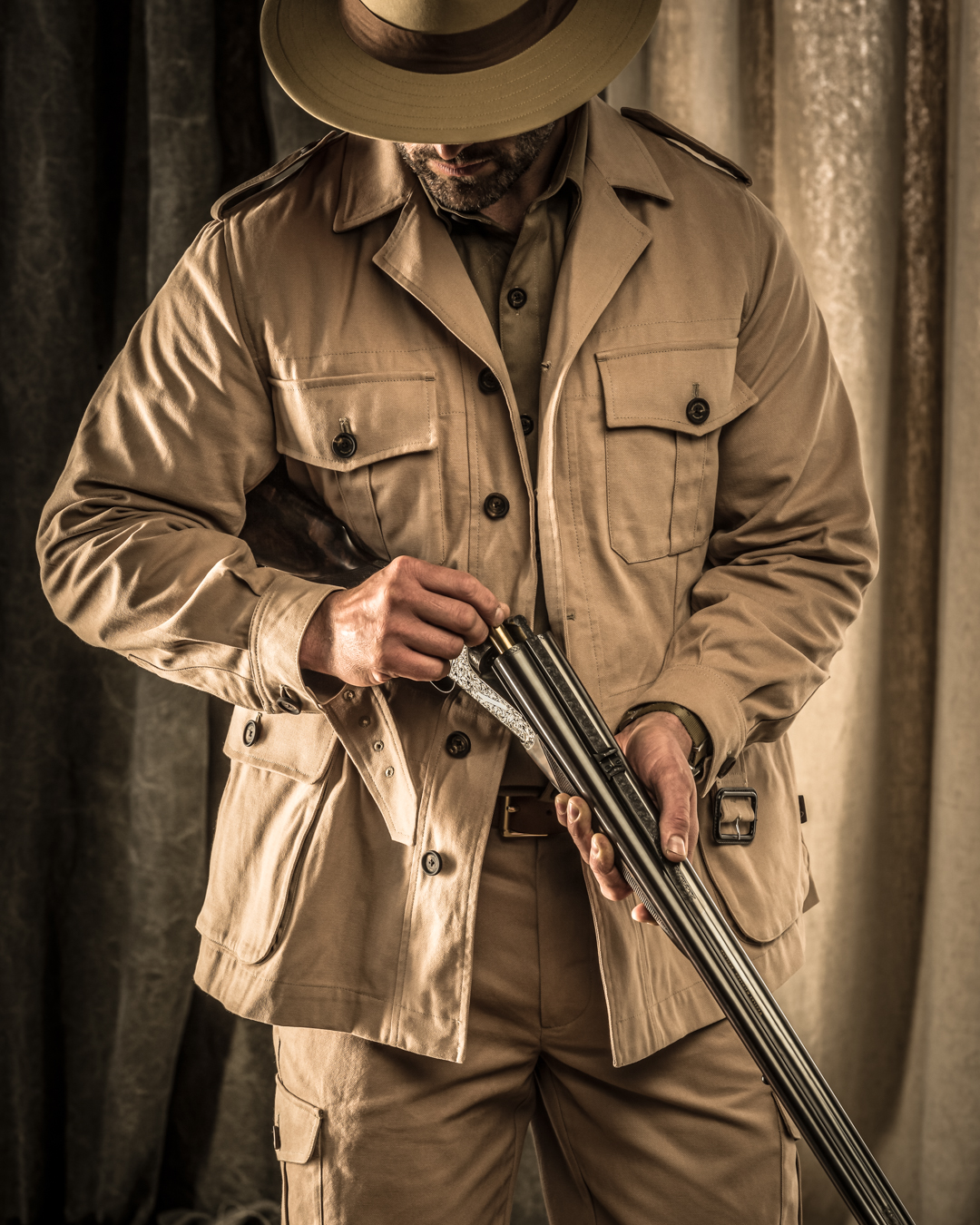

PS. Only with a .500 NE Westley Richards drop lock double rifle!